IN SEARCH OF SCOTTISH ROOTS - Article #1 Archibald MacGregor |

|||||||||||||

| | "The scarcity of provisions, had none become so great, that the men were on this important day reduced to the miserable allowance of only one small loaf, and that of the worst kind… Its ingredients appeared to be merely the husks of oats and a coarse unclean species of dust." |

| | "The persevering and desperate valour displayed by the Highlanders on this occasion is proved by the circumstance, that at one part of the plain, where a very vigorous attack had been made, their bodies were afterwards found in layers three and four deep, so many, it would appear, having in succession, mounted over a prostrate friend to share in the same certain fate." -- ‘Jacobite Memories: Lyon in Mourning’ |

| | “Upon Thursday, the day after the battle, a party was ordered to the field of battle to put to death all the wounded they should find upon it, which accordingly they performed with the greatest dispatch and the utmost exactness, carrying the wounded from the several parts of the field…where they ranged them in due order, and instantly shot them dead” -- ‘Jacobite Memories: Lyon in Mourning’ [x] |

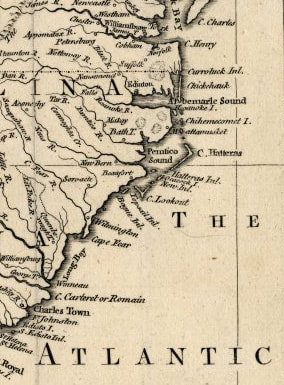

Figure 7: Detailed map of the Coastal & "Cape Fear" region of North Carolina - 1755

Figure 7: Detailed map of the Coastal & "Cape Fear" region of North Carolina - 1755 by William Elsey Connelly

(MacAlpin) MacGregor Family

- F – Ann MacGREGOR. She was born on the 14th of February, 1756, in North Carolina, and died about 1830, in Oil Springs, Floyd County, Kentucky. She married Henry CONNELLY in 1774, in Guilford County, North Carolina. He was born on the 2nd of May, 1752, in Chester County, Pennsylvania, and died on the 7th of May, 1840, in Oil Springs, Floyd County, Kentucky. He was the son of Thomas & Mary (Van HARLINGEN) CONNELLY.

- ANDERSON, Peter. “Culloden Moore and Story of the Battle; with Description of the Stone Circles and Cairns at Clava.”

- ARNETT, Ethel Stephens. “Greensboro, North Carolina – The County Seat of Guilford.” 1955, published by the University of North Carolina Press, Chapel, Hill, North Carolina.

- ASHE, Samuel, A; WEEKS, Stephen B.; Van NOPPEN, Charles, L., Editors. “Biographical History of North Carolina, from Colonial Times to the Presents.” 1906. Volume V, Charles L. Van Noppen, Publisher, Greensboro, North Carolina.

- CONNELLY, William Elsey. “Eastern Kentucky Papers: The Founding of HARMAN’s STATION; with an account of The Indian Captivity of Mrs. Jennie Wiley and the Exploration and Settlement of the Big Sandy Valley in the Virginias and Kentucky.” The Torch Press, Cedar Rapids, Iowa – 1910. See Page 102.

- FORBES, ‘Reverend’ Robert. “Jacobite Memoirs of the Rebellion of 1745.”

- FORBES, ‘Reverend’ Robert. “The Lyon in Mourning; or a Collection of Speeches, Letters, Journal, etc. Relative to the Affairs of Prince Charles Edward Stuart.” By the Rev. Robert Forbes, A.M. Bishop of Ross and Caithness, 1746-1775. In Three Volumes. Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable, for the Scottish History Society, 1895.

- GIBSON, John Graham. “Old and New World Highland Bagpiping.”

- McGRUDER, Egbert Watson (Editor). “YEAR BOOK of American Clan Gregor Society: Containing the Proceedings of the tenth Annual Gathering, 1919.” The William Byrd Press, Inc., Printers, Richmond, Va.

- MURRAY, William Hutchison. “Rob Roy MacGregor: His Life and Times.”

- MOHAN, Lord. “History of England.”

- RAY, Celeste. “Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South.”

- REID, Stuart. “The Scottish Jacobite Army 1745-46"

- SCOTT, Sir Walter. “History of Scotland.” Volumes I & II.

- SPRUNT, James. “Chronicles of The Cape Fear River, 1660-1916.” 1916, 2nd Edition. Raleigh Edwards & Broughton Printing, Co.

- STOCKARD, Sallie Walker. “The History of Guilford County, North Carolina.” 1902, Knoxville, Tennessee; Gaut-Ogden Co., Printers and Book Binders.

- British Battles. http://www.britishbattles.com “The Battle of Culloden 1745”

- Clan MacGregor. http://www.clangregor.org “Glengyle House, Historical Articles and Stories,” by Bob Lundin.

- Crann Tara, Preserving the Culture, History, Heritage & Future of Scotland. http://www.cranntara.org.uk

- Everypoet.com. http://www.everypoet.com - Poems by Andrew Long

- Gen Uki, UK & Ireland Genealogy. http://www.genuki.org.uk - Argyllshire

- National Galleries of Scotland. http://www.nationalgalleries.org

- NLS – National Library of Scotland. http://www.nls.uk - Map of the Battle of Culloden.

- North Carolina History Project. http://www.northcarolinahistory.org – “North Carolina Colony and State Maps

- The Argyll Colony Plus, The Journal of the North Carolina Scottish Heritage Society. http://www.theargyllcolonyplus.org

- The Queen of Scots. http://www.queenofscots.co.uk “Culloden Moor and Story of the Battle,” by Peter Anderson; original published in 1867.

- The Royal Collection; Royal Palaces, Residences and Art Collection. http://www.royalcollection.org.uk

- Figure 1: Charles Edward Stuart (1720-1788) – Picture on Left is a portrait painted between 1739 to 1745 by William Mosman, showing Charles clothed in a tartan jacket, with the garter containing the star and ribbon, and the white cockade displayed on his hat. Picture on Right, by Maurice Quentin de la Tour, 1748. Wearing the blue sash of the Order of the Garter across his breastplate.

- Figure 2: Statue of “Robert the Bruce.”

- Figure 3: The Battle of Culloden, by David Morier. 1746. – Title of the painting: “The Highland attack on the Grenadier Company of Barrell’s King’s Own Royal Regiment.”

- Figure 4: “The Battle of Culloden showing the Encampment of the English Army; At Nairn, and the march of the Highlander’s in order to attack them by night.” Map by John Finlayson, dated about 1746.

- Figure 5: The Battle of Culloden, by Mark Churms.

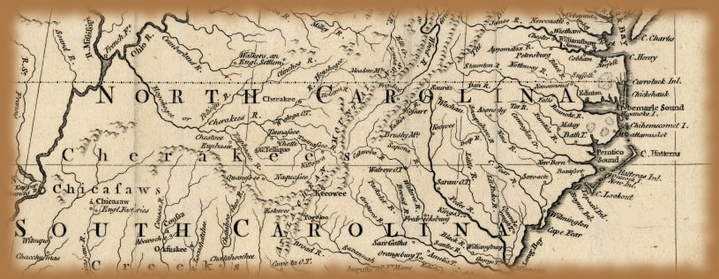

- Figure 6: Territorial Map of North Carolina, dated 1755.

- Figure 7: Detailed map of the Coastal & “Cape Fear” region of North Carolina, 1755.

- Figure 8: The Crest of the MacGregor Clan.

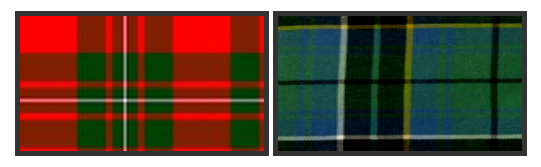

- Figure 9: The Tartan Colors of the MacGregor Clan & Ancient Tartan of the MacAlpine Clan.

- Figure 10: Andrew Lang – “A prolific Scots man of Letters.” (1844-1912); Drawn by Burne Murdock, engraved by J. F. Jungling.

| Archibald MacGregor & The Battle of Culloden Moor.pdf | |

| File Size: | 743 kb |

| File Type: | |

Thank you for this.I am a decendent of Archibald and Eddith through my grandmother Betty Connelly

Thank you for this! I am a descendant of Captain Henry Connelly and Ann MacGregor through their great-great granddaughter Serena Conley.

Very interesting! I am related to Ann and Henry Connelly through Henry, Jr, Peggy Connelly/Richard Caswell Adkins.

Thank you Steven, I enjoyed your research very much. I am Related through John Conely, son of Henry and Ann Connelly. Thank you again

Roy Whitsett

Thank you for putting this together and publishing it. I am a descendant of Henry Connelly and his wife Ann McGregor.

I am also a descendant of Henry and Ann Connelly. Henry was my 6th great grandfather. My grandmother is a Connelly. Excited to find this, and hope to connect with relatives.

Thank you

RSS Feed

RSS Feed